By Barbara Blake Hannah

Finally, the full story of the Ethiopian Prince Alemayu, the son of Emperor Tewodros, who was taken from Ethiopia to England after the Battle of Maqdala, has been told and told well. Andrew Heavens must be commended for using his literary talent to explain details of the life of the boy prince, completely clarifying the mystery that has always surrounded his name and describing his life with words so vivid and descriptive, that at times I felt I was watching a documentary film, not just reading a book.

Heavens begins by explaining that Emperor Tewodros was a brave soldier king who, in an effort to unite the nation under his leadership, led his army to conquer the many Rases who ruled other parts of Ethiopia. The fortress castle of Maqdala stood on top of a precipitous mountain that made it almost impregnable. Here was Prince Alemayu born, son of a beautiful wife who agreed to marry Tewdros in return for him freeing her father from among the many prisoners he kept chained in the castle. Tewodros had asked two British explorers who became his friends, to help improve his relations with Britain’s Queen Victoria by delivering to her a letter requesting a close military association to defeat his Turkish enemies. But after they died, this important letter was delayed by 15 months without an answer, making the Emperor so angry that he captured and imprisoned at Maqdala all the British and Europeans who were then in Ethiopia. It was this group of prisoners that Britain decided to send an army to rescue.

The details of the army sent under Robert Napier, are astonishing. Consider the 42 elephants that were just one small detail of the immense collection of items accompanying the soldiers. Food, clothing, even railway tracks to be laid from the port where the army landed, carrying men and armaments into and across Ethiopia, showed the strength of Britain’s military might. The truths Heavens uncovers with his detailed research show that, faced with the failure of his own cannons to do damage to the British army, and his impending defeat, Tewdros fires his pistol into his mouth. His still-bleeding body is immediately subjected to the first of hundreds of acts of the looting of Maqdala. his clothing is cut into shreds and locks of his long hair render him nearly bald. Halfway through this act of ghoulish theft, one man sketches a picture of Tewdros’s head, giving us the first close-up look at the historic Emperor.

After the battle and subsequent looting, Napier takes responsibility for little Alemayu and his mother, as the British army makes a rapid return to England. Though some stories of this departure gave the impression that the little prince and his mother were either kidnapped or trafficked, in fact Tewodros had several times in the past said he wanted his son brought up in England, to which his mother had agreed. She, sadly, died en route to Aden, and Alemayu was taken on board ship under the care of a very unusual Englishman, Captain Speedy, who becomes a central figure in his life.

Captain Speedy, another explorer who knew Ethiopia so well he spoke Amharic, became the prince’s official caretaker for several years thereafter, a relationship with which the child was happy and which Queen Victoria, to whom the royal child was presented, official approved of. While a previous impression had been given that the Queen had held Alemayu under duress, the book shows she treated him like a caring and loving grandmother, giving him — under Captain Speedy’s care — access to her summer home on the Isle of Wight and frequent visits to her at Windsor Castle. She was forever interested in his welfare, but in details Heavens reveals, the Queen had less power over decisions about life, than the government officials who ruled Britain.

Little Alemayu grows up in England under Speedy’s care. The book shares photos of the young prince, in each of which we can see unhappiness behind his quiet, sad eyes. Speedy and his wife move to India with Alemayu, but when Speedy wants to move to the Phillipines, that move is denied by government decisions, Alemayu is returned to England and efforts made for him to receive a proper English education. He is sent to Rugby school where he endures traditional bullying, then to Sandhurst military school where the bullying becomes brutal and cruel. His inability to acquire the desired level of English education causes those in charge of Alemayu to give up trying to qualify him for a proper job.

Sent to stay with a former tutor in a cold countryside house in the middle of winter, 18-year old Alemayu contracts a bad cold, refuses to eat food and, despite efforts by nurses, doctors and even a brief visit from Captain Speedy, he dies. Considering the boy’s story — the paradise life in which he spent his early years, the shock of witnessing the onslaught on his home Maqdala, the death of his father, then his mother, his move to the very foreign England where his colour and royal birth made him a constant source of attention and racism, his several moves from persons and places, and his eventual brutal experience at Sandhurst — his experiences in England must have made Alemayu decide that his life was no longer worth living. Refusing to eat must have been his easiest way out of all the sadness, mental and physical pain he had suffered in his short life and though various pulmonary diagnoses are given, it seems clear that suicide is the cause of Alemayu’s death. The photo of him in death shows his very handsome face, resting and finally at peace.

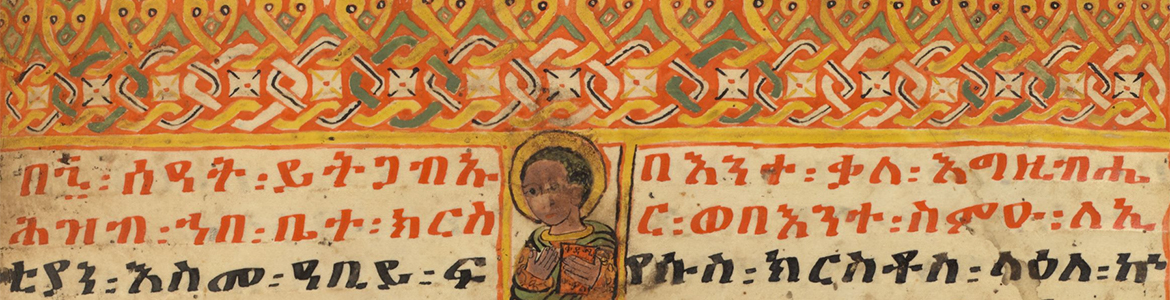

The book does not end there. We learn that Alemayu’s constant wish to be returned to Ethiopia was on the point of being granted, but he didn’t live to know that. The Ethiopians at home and abroad who have tried since then to have Alemayu’s remains returned are told that his tomb is inaccessible, but this is inaccurate. Ras Tafari Makonnen, later crowned Emperor Haile Selassie, visited St. George’s Chapel in 1924, examined his tomb and corrected the inscription by placing an Amharic version of his name on it. Clearly it is not buried and irretrievable. Those who love Ethiopia will not cease asking to have his remains returned. The book lists the various items of booty looted from Maqdala, identifying the British museums and libraries where they are located and how they came to be there. Not all have been found, and some are in private collections, while a few have actually been returned. Some, such as the Ethiopian Orthodox Tabots locked in secret rooms of the British Museum that cannot be seen except by priests, are part of the ongoing request for their return to Ethiopia, as they all should be. The book makes special mention of Rastafari in a chapter about Ras Seymour McLean, the Book Liberator, who removed hundreds of Ethiopian books from British museums and libraries, claiming that he was returning ‘stolen legacy’ to its original owners, and bringing Rastafari energy to the campaign to have all of the Maqdala treasures repatriated.

I deeply congratulate Andrew Heavens for writing this fascinating, well-researched and informative book. It gives a vivid picture of Ethiopia a century ago, providing a link through the young Prince to today’s Ethiopia. Prince Alemayu in life and death is a symbol of Ethiopia’s history and the treasures looted at Maqdala. The story is not over till he and the treasures looted from his father’s kingdom, are returned.

© Barbara Blake Hannah