By John Mellors

In Northern Ethiopia most weddings take place in January and February, after the Christmas fast has ended and before the long Easter fast begins, as this is the low season for agricultural work. An embroidered dress is traditionally given to the bride by the groom as part of her wedding dowry. After use during the wedding festivities the dress is then normally only worn on special occasions such as important religious festivals. In the nineteenth century, visits by European travellers were probably often treated as special occasions, and a chance for the embroidered dress to be worn. This has led to some confusion, and the Ethiopian embroidered dress has often been described as the wear of a ‘fine lady’ or a ‘lady of fashion,’ rather than as a ‘wedding dress.’

© Victoria and Albert Museum

© Victoria and Albert Museum

Embroidered dresses of the above type can be easily dated if the original owner, and the date of their wedding, is known. Unfortunately, this information was rarely recorded when the dresses were collected. The Victoria and Albert Museum, London, has in its collection two embroidered dresses (museum no. 399-1869 and no. 400-1869) that are ‘said to have belonged to Queen Woyzaro Terunesh, the second wife of the Ethiopian emperor Tewodros (Theodore), and mother of the prince Alamayehu’ (Figs. 1-2). The dresses are also said to have been taken by British troops at the siege of Magdala in 1868. So where and when were these dresses made and why should Terunesh possess two ‘wedding dresses’?

Terunesh (later also known as Teruwerk) was the daughter of Ras Wube, who was defeated by Tewodros in 1855 at Derasge in the Simien Mountains in a battle to decide which of them would become emperor. The coronation of Tewodros took place at Wube’s church, Derasge Maryam, a few days later. The wedding of Terunesh to Tewodros, five years later, is surprisingly well documented as several Europeans were present in the area at the time. The best account is given by Henry Stern, in his book Wanderings among the Falashas in Abyssinia (1862). Stern was a British Protestant missionary who went to Ethiopia to try to convert the Falashas, or Beta Israel, to Christianity. He travelled to Ethiopia via Egypt and the Sudan, reaching Lake Tana, where he first met Tewodros, in early April 1860. His first trip was quite short and he left Ethiopia in November 1860.

According to Stern, the Englishman John Bell was instrumental in persuading Tewodros that he should remarry following the death of his first wife, and in bringing Terunesh to Debre Tabor to be married. Stern wrote that John Bell:

was despatched to the Church where the destined Queen and her mother had for several years found a safe asylum against the allurements of vice, and the violence of lawless rebels. Mr. B. himself had to devise the most elaborate plan to protect the bride from the sight of any but female eyes. To do this in a manner so that no malignant and envious tongue should be able to impugn his fidelity to a kind master, he ordered, immediately on arriving near the sanctuary, a wide enclosure to be constructed from the tents, of which he had an ample stock. This being done, the bride, swathed and muffled like a mummy, was led by her mother and a bevy of waiting-women within the fence, where, gorgeously caparisoned mules held by slaves stood ready for her and her nearest relatives to mount. All being again in their saddles, a dozen horsemen rode on in advance to keep the road clear, whilst their leader and the rest waited at a respectful distance till the female cavalcade had filed off, when they also set their steeds in motion and followed in the rear. The etiquette observed on the first day was rigorously maintained throughout the whole journey. At Debra Tabor, the happy lady, who was won without being wooed, and got a husband without ever seeing a lover, met from the King and his numerously assembled subjects the most gratifying and enthusiastic reception.

The wedding took place in May 1860, several months after the usual wedding season and just before the rains started. Hormuzd Rassam, sent by the British Government to Abyssinia in 1864, wrote in his Narrative of the British Mission to Theodore, King of Abyssinia (1869) that Terunesh was 12 years old at the time of her wedding. In contrast, William Simpson, an artist with the British expedition to Magdala in 1868, reported that she was born in January 1850 and so would have only been 10 (The Illustrated London News, 27 June, 1868) at the time of the wedding. Tewodros was born around 1818, so he would have been about 42 years old. The wedding was a full Church wedding, which meant that Tewodros was committed to a lifelong marriage with Terunesh. Stern wrote that:

The King's civil marriage being attested by a jubilant nation, nothing else was requisite to make it lasting and secure than the holy communion, and this the happy pair received in grand state the week following from the hands of the Aboona, who had been specially summoned from Magdala to perform the solemn act. Henry Stern is believed to be the first photographer to go to Abyssinia, and his photograph of 'Aboona Salama, Metropolitan of Ethiopia' is reproduced as a full page engraving in his book. Stern must have photographed the Aboona during the wedding celebrations at Debre Tabor.

Tewodros was said to make sure that his Queen was well guarded at all times. Henry Blanc, who arrived in Abyssinia with Hormuzd Rassam and who was subsequently held captive at Magdala, wrote in his book A Narrative of Captivity in Abyssinia (1868) that:

No one, not even the smallest page, could, under the penalty of death, enter his harem. He had a large number of eunuchs, most of them Gallas, or soldiers and chiefs who had recovered from the mutilation the Gallas inflict on their wounded foe. The queen or the favourite of the day had a tent or house to herself, and several eunuchs to attend upon her; at night these attendants slept at the door of her tent, and were made responsible for the virtue of the lady entrusted to their care.

Blanc added:

He was a very jealous husband. Not only did he take the precautions I have already mentioned, but [...] he never allowed the queen or any other lady in his establishment to travel with the camp. They always marched at night, well concealed, with a strong guard of eunuchs; and woe to him who met them on the road, and did not turn his back on them until they had passed!

Even when she was travelling it was difficult to see what Terunesh looked like. Henry Dufton in Narrative of a Journey through Abyssinia in 1862-3 (1867) wrote how he once saw Terunesh:

Once on this march, I was gratified by a sight of the fair Toronetch, Iteghe or Sultana to the Abyssinian monarch; but as she was muffled up to the eyes with a superabundance of rich garments, my view was confined to the two brilliant orbs, which, if report be correct, have often returned the withering fire of her royal husband's. Theodore gives little love to the beautiful daughter of Oubie, but he is proud of being the possessor of the fairest and most accomplished of Abyssinian princesses.

J. Theodore Bent, who travelled to Aksum in 1893, wrote in his book, The Sacred City of the Ethiopians (1896), about weddings:

Whilst we were at Asmara numerous weddings took place, prior to the austerity of the Lenten fast […] The bride sat in state in an adjoining hut, with a curtain before her, which was raised for our benefit that we might inspect her richly embroidered dress, and give her our best wishes.

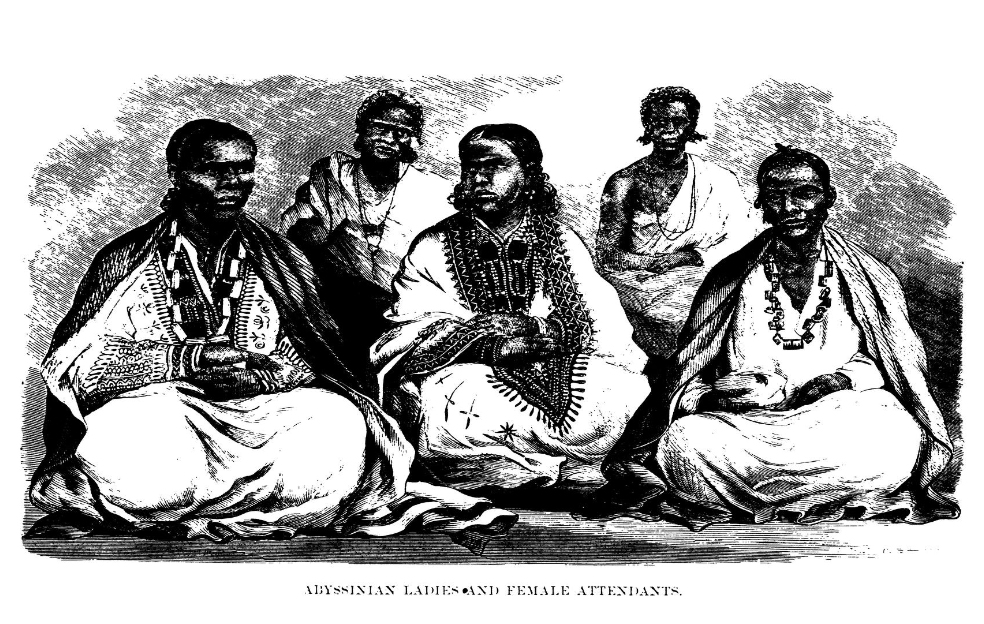

Henry Stern included a full page engraving ‘Abyssinian Ladies and Female Attendants’ (see below) in his book which appears to be the sort of wedding scene that Bent described, showing two ladies wearing embroidered dresses. Close examination of the two dresses in the engraving makes it clear that these dresses are the ones now held by the V&A. This means that the lady in the centre of the engraving must be the normally reclusive Queen Terunesh, wearing dress no. 399-1869 (Fig. 3). Her mother, Woizero Lekiyaye, must be the lady on her right wearing dress no. 400-1869 (Fig. 7). The lady on her left in a plain dress is probably her nurse and the two ‘ladies’ at the back look as though they may be eunuchs keeping guard.

Dress no. 399-1869 would have been made in 1860 for Terunesh, probably in Debre Tabor. In later years the dress has had an extension piece added as Terunesh would have grown significantly during her teenage years. The second dress, no. 400-1869, would have been her mother’s wedding dress, and so would have been made some time in the 1840s, probably near Derasge in the Simien Mountains.

After Magdala, Terunesh, Alemayehu, and Lekiyaye travelled with the British troops on their march back to the coast. Sadly, Terunesh died en route and was buried at Chelekot in Tigrai. The seven-year-old Prince Alemayehu, born one year after the wedding, was brought back to England. Woizero Lekiyaye returned back to Derasge, from where she wrote at least two letters to Queen Victoria enquiring about her grandson, Alemayehu.

****

Originally published in the Winter 2013 edition of The Anglo-Ethiopian Society’s News File magazine.

The Anglo-Ethiopian Society was formed in 1948, with the aim of advancing public education and knowledge about Ethiopia, including its history, culture, art and architecture, natural history and economy.

Go to the Society’s website http://anglo-ethiopian.org/ to sign up as a member and see its programme of events.