The battle

The British and Indian soldiers pressed on, past crowds of thousands of Ethiopians fleeing down the mountain sides. The road twisted up between the two hills onto the wide land bridge of Islamgie. And there at the end of it, finally, was Maqdala.

The soldiers could see around a hundred Ethiopian soldiers and a small group of horsemen charging backwards and forwards across the open ground at the far end of the plain, bright robes flowing behind them. One of them turned his white horse, then galloped straight at the British frontline. And there, the soldiers suddenly realised, was Tewodros, King of Kings of Abyssinia, pulling in his reins, firing his rifle into the air and shouting out a challenge. By this stage he was around 50 years old, out there at the front of his troops, urging them on, channelling the rage of Kasa the shifta.

The monarch and his men withdrew up a twisting path onto the top of Maqdala and shut a heavy set of thorn gates behind them. There was a long pause as the British troops got their artillery into position then opened fire. Every shot missed. There were other pauses as the guns were manoeuvred, and more firing, again with no visible effect.

Through all the noise and smoke it was impossible to tell if anyone was shooting back. Occasionally you could see a single figure between the thorn bushes but there was no other indication of the size of the defence. When the firing stopped there was nothing, silence. Yet another long pause as Napier and his commanders reworked their plans and then, at around 4 p.m., the final charge began. A small storming party was supposed to blow up the gates, under the cover of artillery shells and rifle fire. When they got there, they could not find their powder bags. If there had been any decent force inside, the British would have been stuck. Their soldiers were backed up along the path with no way of pushing forward.

As it was, someone behind the thorny gates managed to get in a few shots, wounding nine British officers and men. Then an Irish private and a drummer got a scaling ladder up against a low section of fence leading up to the gate, scrambled over and took on the handful of Ethiopians defending the entrance from the other side. Close behind them came the rest of the force from the 33rd Regiment of Foot, who charged onto the flat summit.

Tewodros was found lying dead, halfway up a path to the second line of thorn defences. One of his servants later said he had kept under cover with a handful of his most loyal followers during the artillery barrage. He knew it was all over when one shell landed inside the gate and killed one of his generals. Tewodros moved the men further into the fortress then took off a gold-brocaded mantle he had been wearing throughout the day and told his troops to flee. He put a gun in his mouth and pulled the trigger. This time no one stopped him.

The plunder

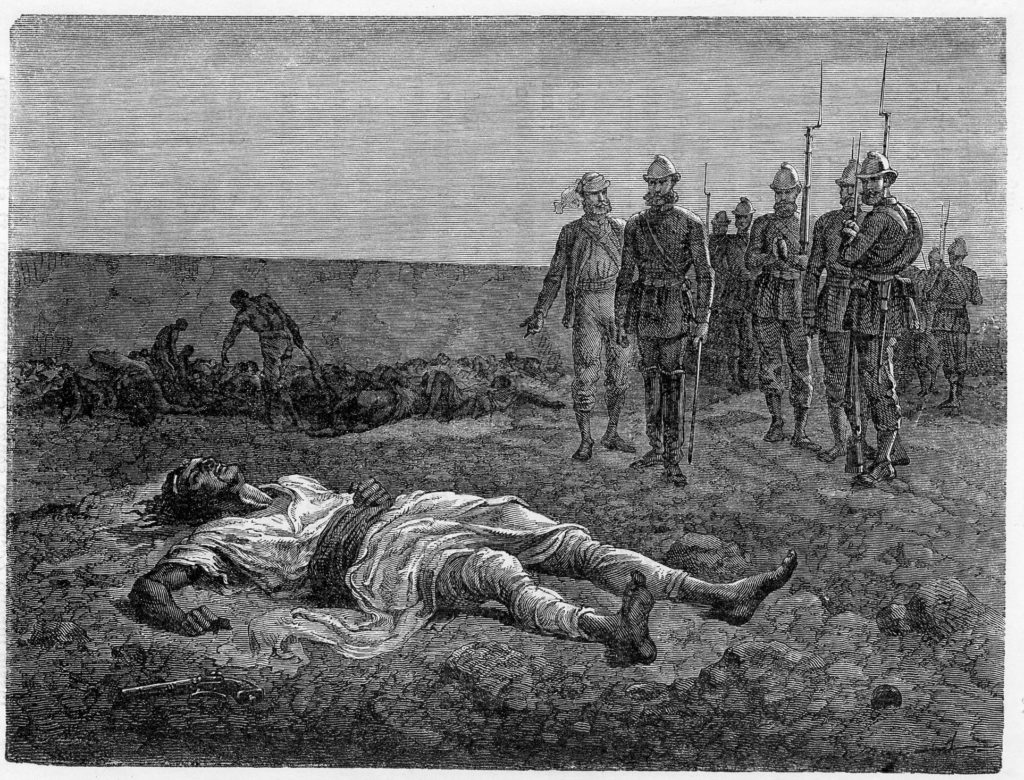

Several engravings later printed in the British press show Tewodros stretched out on the ground, dressed in a dark robe and white undergarment, one arm across his stomach, his feet crossed like a carved effigy on a church tomb. Two small groups of British soldiers keep a respectful distance in the background, taking one last look at their fallen foe. That is not how it happened.

Major-General Sir Charles Metcalfe MacGregor, then a young captain on Napier’s staff, was looking at the body ‘when a rush of fiends, vultures, dressed like Englishmen, broke through and tearing the clothes off the corpse, fought for bits of mementoes!’ (He was sickened, he wrote in his diary. ‘I never saw anything more completely disgusting and unmanly in my life.’) Officers and men jostled around him, pushing each other out of the way to get at Tewodros, who was lying on his back inside the gate. Some ripped off strips of stained material from his robe and ran on. Others paused to dip their pieces of cloth in the blood coming out of his head wound, the ultimate primal battle souvenir, a piece of the enemy. The men were riding on the high of an easy victory after weeks upon weeks of building tension and hard marching.

There had been little actual fighting, particularly on the last day. But the thought of plunder and the rush of conquest was all they needed. The men kept on ripping off souvenirs until the body was a mess of rags, then peeled off in groups to search the huts that crowded the summit. Shouts rang out when one party stumbled onto a storehouse filled with 20-gallon jars of tej, and some eggs. ‘Being awfully hungry we ate them raw,’ wrote another member of Napier’s staff, Captain Cornelius ‘Frank’ James. The regimental order of the marching columns had broken down into total chaos and there was no one at that moment to bring it back into order. One group of men dug frantically in the royal compound, searching in vain for buried gold ingots.

Others ransacked Maqdala’s Church of Medhane Alem – ‘the Saviour of the World’ – pushing past the British Expedition’s own Catholic chaplain, who was doing his best to defend the building. There was a ring of small huts around the main church holding bodies waiting for burial. Two witnesses described how the soldiers ripped off the coffin lids and took what they could find inside, including crosses from the corpses. An observer said one of the bodies belonged to Abuna Salama III, the head of the Orthodox Church, who had come down from Egypt, crowned Tewodros then fallen out with his protégé and died a semi-captive on Maqdala a year earlier. (It might be best to treat this last account with a bit of caution. It would be unusual, to say the least, for a body to lie unburied for so long.)

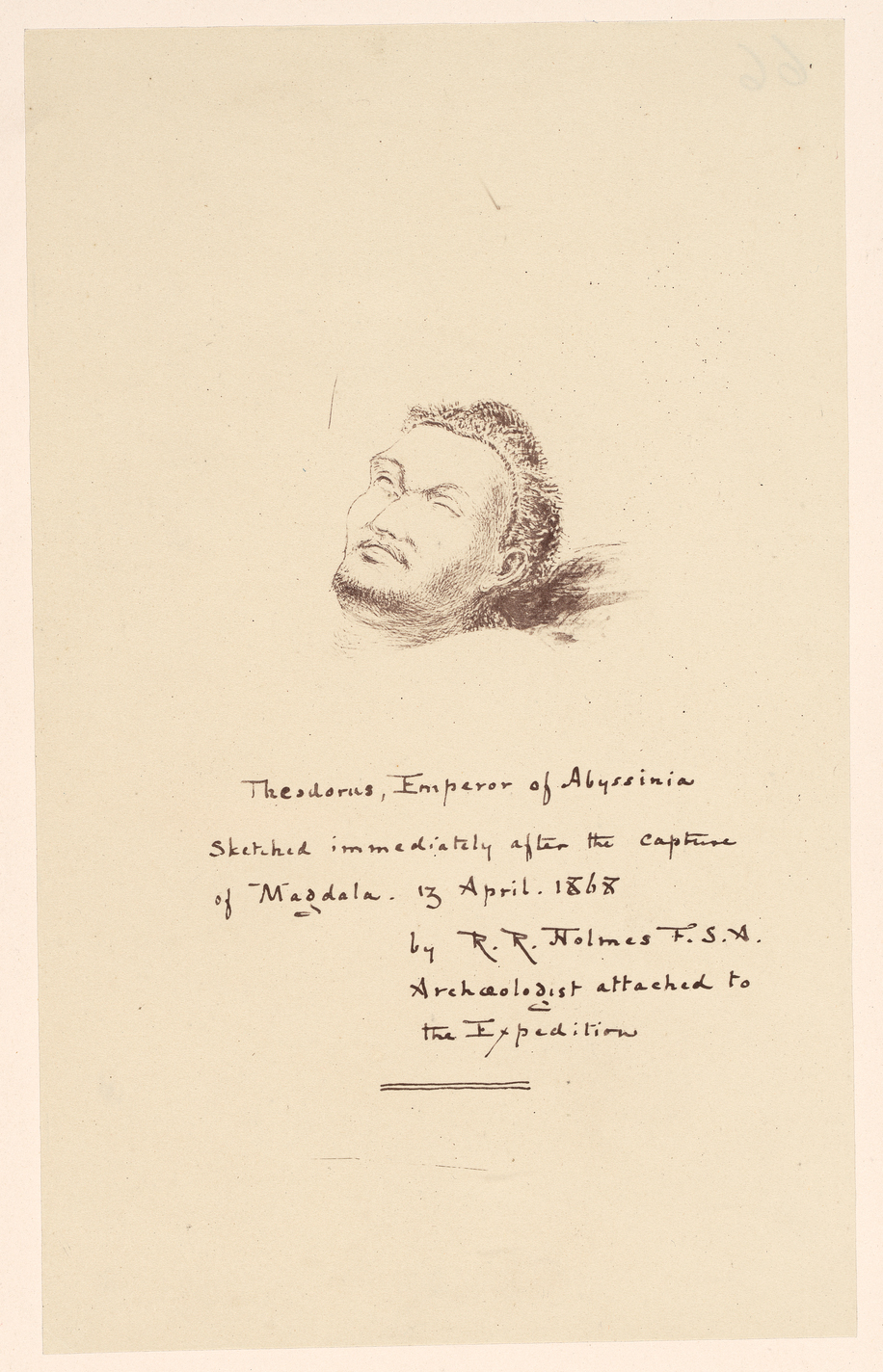

And close behind the soldiers came Richard Rivington Holmes of the British Museum. He made it into the fortress minutes after the main charge and started casting around for loot. A soldier ran past, weighed down by a gleaming golden crown and a golden cup. Holmes did a quick cash deal on the spot and secured his first major treasures. At one point, and it’s not quite clear when, Holmes came across the body of Tewodros and paused to make a quick sketch. It was an unforgiving portrait – only the head, with the torn and mauled clothes conveniently out of the frame. One half-closed eye suggested the trauma of the brain injury – the bullet had passed through the palate and out the back of the head. The hair in the drawing is cropped and torn; clothes weren’t the only mementos taken by the soldiers. Ever the archivist, Holmes annotated and signed his work to establish its provenance: ‘sketched immediately after the capture of Magdala’. It is one of a very few direct portraits of Tewodros, and looks nothing like the superhero graffiti in Addis or, of course, the racist caricatures in Punch. His true face was captured forever moments after his death, the ultimate defeat.

After they had emptied the treasury, drunk the tej and ransacked thechurch, some of the soldiers, according to the anonymous correspondent writing for Germany’s Allgemeine Zeitung, turned to the Ethiopian women and girls left on the summit. ‘Their silver necklaces, arm and ankle bracelets were torn from them, even their clothes,’ read the report. The soldiers ‘feasted on the sight of the defenceless creatures’ and committed ‘disgraceful acts … that cannot be named’. You could dismiss this as slander printed by a paper from one of Britain’s foreign ivals. But there are hints in other accounts.

Tirunesh and Alamayu – and the ever-present Yatamanyu – had lain low during the bombardment and the final battle and eventually tried to seek refuge in the Europeans’ former prison huts. At one point in the melee, one soldier slapped Tirunesh on the back and bawled out in scrambled Arabic ‘Tédros … mafeesh’ – effectively ‘your husband is gone, you’re on your own’. One reporter on the scene said the soldier was trying to congratulate her, as in ‘at last you are free of that monster’. It is hard to imagine her taking it in that spirit. Once the women and the child got to the huts, someone had the presence of mind to post a sentry at the door to protect them. But some of the soldiers forced their way in and pressed around the young queen. ‘Luckily Mr. Rassam and an English officer came in time to save her from further outrage,’ wrote the expedition’s geographer Clements Markham.

Rassam, the former captive who had twice promised to look after Tewodros’s family, had come back up to the summit for one last look at his old home. He and the officer cleared out the soldiers and set up a stronger guard. Alamayu must have been close by and seen it all.

As the afternoon wore on, the summit ‘presented the appearance of an immense curiosity shop which had suffered severely from an earthquake’, wrote Captain James in his diary. The correspondents on the scene competed to come up with the longest list of the plunder scat-

tered around them.

‘In one of the tents was found the Imperial standard of Ethiopia – a lion rampant, of the tribe of Judah, worked in variegated colours,’ wrote the clear winner in the list-writing contest, Henry Morton Stanley. ‘In another was found the Imperial seal, with the same distinctive figure of a lion engraved on it. A chalice of pure gold was secured by Mr. Holmes … The Abuna’s mitre, 300 years old, of pure gold, probably weighing six or seven pounds troy weight; four royal crowns, two of which were very fine specimens of workmanship, and worth a round sum of money; were worthy things to be placed in the British Museum.’ He was just getting started.

‘A small escritoire, richly ornamented with mother-of-pearl, was found also, full of complimentary letters from European sovereigns, and state papers; besides various shields of exquisite beauty.’

The presents and messages that European powers had sent in the days when they were courting Tewodros were piled up on Maqdala and taken back. Stanley continues his list:

“There was also an infinite variety of gold, and silver, and brass crosses, and censers, some of extremely elegant design; golden and silver pots, kettles, dishes, pans; cups of miscellaneous descriptions; richly chased goblets of the precious metal; Bohemian glasses, Sèvres china, and Staffordshire pottery; wine of Champagne, Burgundy, Greece, Spain, and Jerusalem; bottles of Jordan water; jars of arrachi and tej; chests full of ornamental frippery; tents of rose, purple, lilac, and white silk; carpets of Persia, of Uschak, Broussa, Kidderminster, and Lyons.”

The wine, arrachi (the distilled drink araki) and tej did not last long. The troops were parched after their days of scrambling and battling. There is no record of any fragile Sèvres china or Staffordshire pottery surviving the melee, though the King’s Own Royal Regimental Museum in Lancaster does still have one ‘18th Century European glass tumbler’ in its Maqdala display case.

Stanley continued:

Robes of fur; war capes of lion, leopard, and wolf skins. Saddles, magnificently decorated with filigree gold and silver; numerous shields covered with silver plates; state umbrellas of gorgeous hues, adorned with all the barbaric magnificence that the genius of Bejemder and Gondar could fashion; swords and claymores; rapiers, scimitars, yataghans, tulwars, and bilboes; daggers of Persia, of Damascus, and of Ind, in scabbards of crimson morocco and purple velvet, studded with golden buttons; heaps of parchment royally illuminated; stacks of Amharic Bibles; missals, and numberless albums; ambrotypes and photographs of English, American, French and Italian scenery; bureaus, and desks of cunning make. Over a space growing more and more extended, the thousand articles were scattered until they dotted the surface of the rocky citadel, the slopes of the hill, and the entire road to camp two miles off!

Stanley, writing for an American newspaper, and the anonymous correspondent of the Allgemeine Zeitung were free to describe the excesses.

Other frank accounts came from the men’s private diaries and letters, never meant for publication. But the plundering posed a problem for all the British journalists and chroniclers gathered on the summit to bear witness to the victorious conclusion of a noble rescue mission. How to squeeze the loot into their narratives? Some chose not to mention it at all. The ones that did typically fell back on three techniques, all used concurrently in the work of the anonymous staff officer reporting for Edinburgh’s Blackwood’s Magazine.

One, they could shrug and dismiss the plunder as trash, barely worth mentioning so barely worth mourning. ‘Hardly anything of value was found in the place,’ the staff officer wrote. ‘A trumpery crown [was] the most costly object,’ wrote Sir Charles Metcalfe MacGregor. ‘No booty found at Magdala’ was how Napier put it in a telegram sent back from the final battlefield.

Two, they could say the plunder was already stolen – and stealing a stolen thing cancels out the crime. ‘The collection was, at all events, a most discreditable one to its late owner, since it consisted partly of crosses, paintings and sacred vessels plundered from Christian churches, and partly of the weapons used by himself and his soldiers in mauling the priests,’ wrote the staff officer.

Three, they could affect their own air of disdain and write the whole thing off as a base aberration: ‘The way that some men will scramble for a piece of silk or an old sword, such as few gentlemen would think worth carrying home if found anywhere else, merely because it happens to be booty, is a remnant probably of the old predatory instincts of the species.’

Towards the end of the day, Napier took in the scene at the summit and, for all his talk of ‘no booty’, posted guards at the gates to restore some sense of discipline and stop anyone taking plunder down to the British camp at the foot of Maqdala. Orders were issued to halt the unlicensed, drink-fuelled pillaging. The senior officers had something more licensed, more respectable in mind.

That night, the men were told to start handing over anything they had grabbed. When that order was ignored, they were lined up and searched. The only treasures they were allowed to keep were things they had taken ‘at the point of the bayonet’, as in things they had grabbed off an enemy during active combat – a kind exemption for acts of ultra-violence. The fact that there was actually very little hand-to-hand combat at Maqdala did not stop the British soldiers walking away with a good number of Ethiopian muskets and shields and other pieces of memorabilia. Stories later spread of one member of a regimental band who had got a handful of jewels back to Britain by covering them in mud then sewing them into a cricket ball.

Colonel (then Ensign) W.A. Wynter told his son years later he had had to hand over a silver processional cross that he had found. He made up for the loss by buying a large rhinoceros-hide shield from a passing British sergeant who assured him a bayonet had been involved in its acquisition. (The cross, according to Wynter, later turned up as a centrepiece at the Royal Artillery Mess at Woolwich.) Even Holmes handed over his crown and chalice, on the understanding that they could be kept to one side, taken back to Britain and saved for the nation. The British nation, that is.