What: One tabot, hidden in an altar

Where: Westminster Abbey, Dean’s Yard, London, SW1

Here’s how to find some buried treasure in the centre of London.

Forget the explorer’s gear, the hat, the whip. You don’t need to look like Indiana Jones for this. Dress like a tourist and head to Westminster Abbey, across the road from the Houses of Parliament. Hand over the exorbitant entrance fee and follow the crowds past the tombs of empire grandees, prime ministers, princes and poets.

Towards the end of the trail, you will come to a chapel that holds the remains of King Henry VII and his wife Elizabeth. Wait for the red-robed guards to move away, edge past the velvet ropes at the altar and poke your head around the back. And there you will see … well, at first glance, not very much.

Push your luck and edge a bit further round, getting your body into the gap between the altar and the tomb. You should be able to make out two windows, a few inches wide, set into altar’s rear wall.

If the guards still haven’t spotted you, peer into the first one on the left, and you are going to be disappointed. The window is a sheet of something like perspex over a small rectangular chamber cut into the back of the altar. But someone has smeared paint over the inside of the pane, blocking the view. Below it, on the wall, there’s a carved message describing what’s hidden inside – a fragment of Canterbury Cathedral bearing the marks of the fire which destroyed parts of it in 1174. A dig through the archives will tell you the fragment is a blue-green stone, a piece of jasper, left inside Henry’s altar like an ancient lucky charm. But you will have to take their word for it. You can’t see anything in the murk.

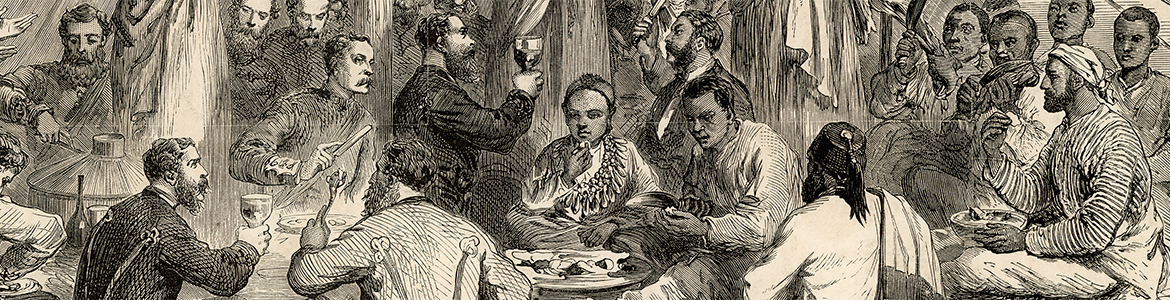

Next to that there’s a smaller window, just as badly besmirched. The carved label and the archives tell you there’s a fragment of mosaic lying in the alcove behind, taken from a Greek church in Damascus that was destroyed during a massacre of Christians in 1860. Another wrecked relic sealed inside the altar, forced to share some of its magic with Henry’s monument. You can’t see it through the paint, and it is not what you are looking for anyway.

Beyond that, can you see empty space past the two windows, the space where a third window could be? Get the light right and you should indeed see the faint square outline of a slightly larger, squarer opening. Someone has blocked it off completely with a sheet of hardboard, and then painted it over the same colour as the surrounding surface – almost as if someone in the Abbey was trying to hide something.

The only clue to what is buried behind that barrier is the remains of another inscription just below it. The carved words have been filled in with plaster or paint. Get close up and you can still see the shape of the letters.

They spell out the message “…brought from Magdala in 1868“.

The abbey’s refusal to budge looks a little ungrateful when you walk on to the abbey’s sanctuary of the Quire, close to the high altar, and find two presents, given freely by Ethiopia. One is a silver gilt processional cross sent by Emperor Menelik to mark King Edward VII’s coronation in 1902 and the other is a cross carved out of a large ivory tusk given to the abbey by Ras Tafari Makonnen, Prince Regent, later Emperor Haile Selassie, in 1924. Read more about them on the website of the Anglo-Ethiopian Society.